Ovens and Murray Advertiser

Saturday, 30 March 1901

THE EARLY DAYS.

An old colonist's memories.

An elderly lady, who was born in Hobart in April, 1839. and arrived in Melbourne in the following December, recalls some of her early recollections as under : —

I can recall wnen there was neither coal nor gas in Melbourne, when they had to bring the water in carts from a distance of five miles up the Yarra ; when there were no -roads, no footpaths, no gaol, no hospital, not even a Treasury. I can remember. too, when the foundation stone of the first Prince's Bridge was laid, and a bullock was roasted whole on the site of the Elephant and Castle, opposite to the Melbourne Hospital. I can also remember when the first schooner was built and launched on the south side of the Yarra.

My father was a member of the first Temperance Band in the city, under the baton of Mr. Tickell, and my mother and he were present at the first execution that took place in Melbourne, when three men and a negro were hanged in the open, just where the Melbourne Gaol stands now.

My mother then lived in a wattle and dab hut close to Mrs. Bateman's cottage on the Hill. Messrs. Webb and Slattery were the first builders, and the Rev. Father Terry, of St. Francis's, was the first priest. The first pottery was at Burnley, and the first lawyers I can remember were Mr. Stephen and Mr. Redmond Barry. The blacks used to come in and cut wood for us for a shin of beef, and gave very little trouble.

I can remember, too, the first riot in the city, outside an hotel at the corner of Little Bourke and Swanston streets, when windows were broken and flags torndown, and Father Terry came down and dispersed. the mob.

I have also a recollection of Governor Latrobe and his house near Jolimont, and Murphy's Brewery in Little Collins-street, where as a little girl I used to buy yeast.

My father built the first hotel in St. Kilda— the Royal— afterwards Mooney's. Implanted also in my memory are the names of Mr. Heales, coachbuilder, in Exhibition-street— afterwards a member of Parliament, and Drs. Howill, Wilkie and Black.

I can remember, too, the first lock-up in Spencer street, for I got lost when a child, and I was taken there, while the bellman was I proclaiming my loss through the town.

My mother and father, the late Catherine and Samuel Morley, were married in Hobart, and at the time of their death - four years ago - they had thirteen children, thirty-nine grand-children, and forty-four great-grandchildren.

Category: history

Wharf Brewery, Melbourne. 1858

The Australasian

Saturday, 2 May 1936

PASTORAL PIONEERS

By R.V.B. and A.S.K.

JAMES MURPHY

ARRIVING at Port Phillip with his brother John in 1839, James Murphy made arrangements to go straight into the country in search of a pastoral run, but John persuaded him to remain in Melbourne, for a time, and to look carefully into the risks of squatting ventures before risking his capital.

John started business as a brewer in Flinders street west. James accepted a clerkship with the Port Phillip Auction Company, and in 1844 he also set up as a brewer, opening the Wharf Brewery.

For about a year the brothers were competitors, but in 1845 they joined forces, and carried on their brewery business in Little Flinders street west. James, however, still cherished a desire to take up pastoral country. He made several trips inland, and in 1848 he acquired Konagadarra from George Newson.

Konagadarra, on the Saltwater, turned out to be a valuable property, but Murphy parted with it to W. J. T. Clarke before he realised its true worth. Afterwards he went into partnership with W. R. Looker. Murphy and Looker then bought Caragcarag, Colbinabbin, Corop, Tongala, and Lower Moira from the widow of Edward Curr, the father of separation.

They also added Stewarts Plains, a subdivision of Boramboot, to their holding. Stewarts Plains was taken over from John Clarke.

The Murphy-Looker pastoral partnership flourished for a few years, but in November, 1854, it was decided to dissolve the partnership. Murphy took over all the runs. Subsequently he sold Caragcarag, Colbinabbin, Corop, and Stewarts Plains to John Winter, and Tongala to Patrick O'Dea. Lower Moira he retained till 1857, when he transferred this property to Frederick Bury and Peter Cheyne.

In 1853 James Murphy was elected to the Legislative Council, and he remained a member of the council till the advent of Constitutional Government in 1856.

[This series of articles was begun in "The Argus" on August 14, 1934, and was transferred to "The Australasian" on October 6, 1934.]

Mount Alexander Mail

Thursday, 27 April 1865

THE WHARF BREWERY, situated on Flinders street, west, lately in the occupation of Messrs Jno. Bellman and Co., having a frontage to Flinders street and Flinders-lane, and consisting of nearly one acre of ground, on which is built a substantial brewery, fitted up with engines, coolers, mash tubs, vats, and every requisite for the trade, together with malt-houses, stores, stables, &c. This is one of the most complete breweries in the colony, and adapted for carrying on an extensive business on an

economic scale.

Apply to F. J. M'Dougal, 100 Bourke-street, west Melbourne

Australian Town and Country Journal

Saturday 22 November 1879

A Leading Industry

I don't think any business has made such strides in Australia as the brewing of beer; and it is matter of fact that in all the colonies, brewers have almost without exeption made fortunes.

I'm old colonist enough to remember when Murphy's brewery was the only one in Victoria; and many a year after that, Tooth's stood almost, if not quite, alone here; but now every town has its brewery, and all the proprietors do well.

The tase for colonial ale and porter was developed in Victoria more extensively and very much earlier than here; for the people of New South Wales continued in their allegiance to "British Beer " long after "Colonial" was the principal malt liquor of our southern neighbours; and the ale of Castlemaine became an extensive article of commerce among us, almost before Sydney had more than a second brewery of her own.

Then, there was the Hobart Town ale, for which several agencies were established here; and long before that - two or three and twenty years ago - the names of Elliott Brothers, and Glasgow and Thunder, two prosperous brewery firms, were household words at Bendigo.

There had been a brewery years ago on Elizabeth-street; but, before my acquaintance with Sydney, it was in ruins; and Tooth and Co. reigned supreme. Now there are five or six breweries, and all driving a roaring trade; so that, clearly, colonial ale must have taken a hold on the Sydney palate.

Going down Castlereagh-street the other day I turned into Henfrey and Co's brewery, to see Mr. Herald, a partner in the firm, on some business; and I was glad of a look round, as I had not been there since long before the late Mr. Henfrey's death, when it was a large soda water factory, but small as a porter brewery.

And what a change to be sure, a few years have made, for now there is an immense business doing, not only in aerated waters and cordials, but in bottled porter, which is brewed twice a week, to the extent of about 600 dozon each time, all of which is consumed in the hotels.

I tasted some that had been in bottle for three months, and thought it very good - sharp and nice, without being as heavy as English.

No doubt the excellence of the porter arises in a great measure from the brewer being one of the partners.

The soda water machinery is extensive, and fitted with all the latest improvements. One Hayward-Tyler double action beam machine, when worked at both ends, turns out 600 dozen in the day time; and it can be worked by four bottling racks, when it bottles double the number of half bottles, that are now coming so generally into use.

I was told there is only one other similar machine in New South Wales. Another Hayward-Tyler machine, a single action one, is there, to which is fitted a bottling rack made by J. Stevens, of Sydney. This machine, which supplies two bottling racks, will bottle off 700 dozen small, or 500 large in tho day.

Having had the working of these machines explained to me, we next visited the cellars, where are stored the cordials and wines, made in the establishment, together with the strong syrups that form the foundation of all these; and here are to be found all conceivable descriptions of cordials, and balms, and syrups, and liqueurs, that ever were made in a colonial manufactory.

The great secret appears to be in the art of boiling the sugar, so as to make a clear and bright syrup; and in this preliminary operation, fifty pounds worth of sugar is required to fill the simple syrup tank once every week.

There are all sorts of conveniences for loading the carts; and six good harness horses are employed in the business.

Before leaving I was shown a handsome trophy which the firm were going to exhibit in the Garden Palace; but as this was not in show order I must leave it to speak for itself in its representative capacity.

What struck me especially was the scrupulous cleanliness of everything in the place, which is certainly remarkable, when it is considered that all sorts of sticky goods aro continually in use; and that as many as forty hands are employed.

The business seems to go on with the regularity of clockwork.

Villiers Pearce: A Convict’s History – Distressing Narrative

Stumbled across this fantastical story in the Australian newspaper archives.

Villers Pearce was either very unlucky or the Victorian version of Roger Kint, who famously fabricated the story of Keyser Söze to escape jail in the 1995 film The Usual Suspects.

Geelong Advertiser and Intelligencer

Tuesday, June 13 1854

A Convict’s History - Distressing Narrative

Villiers Pearce was put to the bar before Mr Corrie at Clerkenwell, on Saturday, on remand charged that, having been convicted and transported for felony, he was at large without license before the expiration of his sentence.

Seven years ago the unfortunate accused was convicted of forging the signature of the Marchioness of Queensbury to a cheque which he presented for payment at Messrs. Coutts’ bank, where he was given in charge, the forgery being at once detected, and he was ordered to be transported for ten years.

Five months ago he came to London, and was living in obscurity with his children, when, through some family dispute, his hiding-place was made known to Sir Richard Mayne, the Commissioner of Police, and on Sunday he was apprehended, and remanded from the above court to procure his former conviction.

That evidence had been given against him, and on being asked by Mr Corrie if he had anything to say, as it was his duty to commit him for trial at the ensuing Old Bailey Sessions, the prisoner, who was extremely agitated and seemed overwhelmed with remorse thanked the worthy magistrate, saying his history was a sad one indeed, and he hoped the statement he was about to make might be placed in the depositions, so that the judge and jury by whom he would be tried, should become aware of the severe sufferings and privations he had endured.

The worthy magistrate kindly informed that his wishes should be complied with.

The prisoner then said - At the period of the offence for which I was convicted I was in the most acute penniary distress, with a wife and large family of children. A series of misfortunes, the most heavy was the death of my second wife, by which I lost an annuity of £150, with a great falling off, notwithstanding all my exertions of my occupation, brought about unduly the distress in question. Previous to the commission of the offence I had through life bourne an irreproachable character.

In early life, from 1818 to 1822, I held some most responsible appointments in Jamaica and other West India Islands; from 1829 to 1834 I held the appointment of magistrate’s clerk, and postmaster at Bong Bong in New South Wales, and afterwards was superintendent of large farms at Bathurst, over the Blue Mountains, in the same colony. At the latter period I had a wife and family of young children; the former a most amiable partner whom I had the misfortune to lose in 1838, leaving me with seven young children.

My connections are most respectable: my late father was an officer, and of very meritorious services, and my eldest brother is at present a major in the Royal Marine Corps.

I was convicted in 1846; was three months in the Millbank Penitentiary in solitary confinement, subsequently was three years and two months in the Warrior convict-ship, at Woolwich, and I was sent abroad in March 1850. At Millbank, and at the hulks I had the best possible character.

On my arrival at Hobart Town I had a ticket-of-leave, which I retained until I left the colony, never having forfeited the same for a single day by any insubordination. My motive in leaving Van Diemen's Land was to proceed to the gold diggings in the hope I might be successful, and better the condition of my family at home, who are in very impoverished circumstances; but, although my exertions were great in California, Victoria and New South Wales, I was unsuccessful.

It is true I made occasionally some money, but I was robbed of it on the roads by bushrangers, and was frequently illused and robbed at Melbourne and Geelong by the worst of characters. I was shipwrecked twice, and once burnt out at sea; the first time in Torres Straits, between New Holland and New Guinea, on a reef of coral rocks. Upon this occasion I lost between £70 and £80, and all my luggage, eleven of us only getting ashore out of a ship’s company of 27, chiefly Lascars, Malays, and Chinamen. After thirty days of great suffering and privation we were picked up by an American whaler, and ultimately reached Sydney.

I was subsequently wrecked in a brigantine called The Triton, in going from Melbourne to Adelaide, and then lost all I possessed in the world, having had another very narrow escape of my life.

In returning from San Francisco to Melbourne, in a vessel called The White Squall, she caught fire, and we were obliged to abandon her and take to the boats; but a great number of the crew and passengers perished, the survivors in the boats reaching Tahiti in about eight days, in a state of great exhaustion, many of whom afterwards died from the effects of the same.

I again reached Melbourne, and after recovering my health in the hospital I went to Forest Creek and many other diggings, where I obtained some wealth, and, in returning with it to Melbourne, the last time from Forest Creek, I was attacked by bushrangers armed with revolvers, most cruelly beaten, stripped, and robbed of all I had.

Eventually, while in Auckland, I saw a barque bound for England, in want of hands. The temptation was too great, for I had long mourned to reach my dear family; and I shipped myself as ordinary seaman, and assistant steward, and we left the settlement in July, with a miserably crippled ship’s company, and made a very severe passage around the Cape, losing masts, sails, rigging, boat, bulwarks, stanchions, and many of the crew from the yardarm; and finally we reached England in September last, after a most awful passage of four months and 26 days.

Under all these circumstances of my present unhappy condition, I humbly hope that the legislature will humanly consider the long, severe, and various description of punishments I have undergone since my conviction, and I would also most humbly and respectfully call the attention of the authorities to the fact, that the offence for which I have so severely suffered was my first deviation from strict rectitude; also, that it was only required of me by the then regulation of the convict service that I should serve five years on the public works at Woolwich.

If I had completed the remainder (20 months) I should have been discharged a free man. I will further add, that at the time I left Van Diemen’s Land (six months after my arrival), I was entitled to a conditional pardon, which would have left me free to leave the colony.

Therefore, I fervently implore the government to have compassion on me, for the sake of my numerous and respectable family, for my great mental and bodily sufferings, and for my present weakly, worn-out, debilitated state of health.

The recital of the extraordinary sufferings of the unhappy man excited much sympathy in everyone present. Having signed the statement, the prisoner was fully committed to Newgate, the magistrate humanely observing that he hoped his punishment would be light.

On Wednesday the prisoner was brought up for trial at the Central Criminal Court, when, owing to a clerical error in the indictment, he was acquitted.

A discussion then took place as to what was the best course to be taken with regard to the prisoner, it being stated that if he were discharged he might be again pounced upon by the police for the sake of the reward that was paid for the apprehension of escaped convicts.

Eventually the prisoner consented to remain in Newgate until the application could be made to the Government on his behalf.

- Bell’s Messenger, March 4.

Villiers Pearce’s remarkable story piqued my curiosity. Was he telling tall stories to soften up the judge or did he really get transported, shipwrecked, robbed and left destitute ?

Luckily, he has a very unique name – there can’t be that many Villiers Pearces around.

I quite like a bit of historical detective work, so I had a quick hunt around online to see if – 170 years later – I could find out who he was and verify any of his claims.

Here’s what I found:

Villiers Pearce was born on 25 February 1802 in Westminster, London. Thomas John Pearce (1776-1837) and Maria Creswell were his parents.

Reading between the lines, he seems to have been a bit of a chancer, with a gift for story-telling and an appetite for risky, reckless ventures. He seems to have been a volatile, impulsive character who believed he could talk his way out of anything.

He worked variously as a postmaster, magistrate’s clerk, farm superintendent and as a journalist.

He married at least three times:

- Emma Louisa Priddle (1804-1838). They married in St Pancras Old Church, London on 9 January 1825 and had, at least, 2 children:

Emma Louisa Pearce (1828-1893)

Villiers Charles Pearce (1830-1919)

2. Catherine O’Connor (1811 – )

3. Sarah Scott ( – 1841)

His convict record states he had 9 children.

Name: Villiers Charles Pearce

Gender: Male

Baptism Date: 23 Sep 1830

Baptism Place: St Marylebone, Westminster, England

Father: Villiers Pearce

Mother: Emma Louisa Pearce

Church of England Births and Baptisms, 1813-1923

In 1830, Villiers Pearce sailed from London to Sydney on the Sovereign. A ship of 398 tons captained by Master McKellan.

They left London on 28 November, docked in Cape Town on 21 December, and arrived in Hobart on 29 January 1831.

On 12 February 1831, the Sovereign left Hobart for Sydney. You can see the original record of the ship’s departure in the Hobart Register of Ships’ Clearances (with lists of Crews and Passengers) here. The register records Villiers Pearce travelling with his wife and one Edmund Pearce, who might be his brother.

By March 1831, Villiers Pearce had made his way inland from Sydney to Sutton Forest (map), where he was appointed Clerk to the Bench of Magistrates.

The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser

Thursday, 10 March 1831

Government Notice

COLONIAL SECRETARY'S OFFICE, SYDNEY, 8th MARCH, 1831.

HIS EXCELLENCY the GOVERNOR has been pleased to appoint Mr. VILLIERS PEARCE to be Clerk to the Bench of Magistrates at Sutton Forest, in the room of Mr. LOWE, resigned.

By His Excellency's Command,

ALEXANDER M'LEAY

Six months after taking up his post as Clerk of the Bench of Magistrates, Villiers Pearce acquired a plot of land in the newly created settlement of Berrima.

Berrima was established in May 1831 as the ‘site marked out for a township along the new line of the great South Road in Sutton Forest district upon the WingeeCarrabee river’.

Berrima is less than 10 miles from Sutton Forest and, as a local official, Pearce would have been well placed to acquire land in areas.

The plot was described in a subsequent notice in the Government Gazette.

New South Wales Government Gazette

Wednesday 21 October 1840

Case No. 795.—Villiers Pearce, of Berrima, representatives of .—Two roods, County of Camden, parish of Berrima, town of Berrima, allotment No. 4 of section No 3 ; bounded on the west by 1 chain of Argyle-street, bearing north from the north-west corner of allotment No. 4 ; on the north by a line east 5 chains ; on the east by a line south 1 chain ; and on the south by a line west 5 chains.

This allotment was located on an order of Governor Darling, dated 21st October 1831, in favour of Villiers Pearce, who has left the Colony, and whose assigns and representatives are to shew to whom a Deed of Grant should now issue. The description was inserted in the Gazette notice of 29th June, 1839, in the name of the promissee.

In 1832, Villiers Pearce was sued for libel by Robert Wardell, his employer. Robert Wardell was the founder of The Australian, Australia’s first independent newspaper, and was a prominent Sydney lawyer.

Pearce seems to have sent a poison pen letter, alleging a sexual scandal involving Wardell and the wife of his clerk.

The Sydney Gazette takes up the story,

The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser

Thursday 16 August 1832

Police Report

LIBEL - ...Dr Wardell who deposed that about eighteen months ago, the defendant [Villiers Pearce] arrived with his wife and family in the colony, and introduced himself as a relation, in consequence of which he was induced to place him in charge of one of his up-country stations.

His conduct, however, was so dissatisfactory, that he discharged him, a circumstance which seemed to have excited his bitterest feelings.

Three letters, all of which he could prove to be in the handwriting of the defendant, had been sent, one through the medium of the post, addressed to himself, one through the same channel, addressed to Mr Foster, and a third by a messenger, addressed to a branch of his household at Petersham.

The Doctor then read the three letters, which were certainly any thing but laudatory…

A month before the libel trial came to court, Emma gave birth to a son.

The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser

Saturday, 15 September 1832

BIRTH

On the 13th instant, in George-street, EMMA LOUISA, the wife of Mr. VILLIERS PEARCE (formerly of the Royal Navy, and late of Bong Bong, in this Colony), of a son, being her fifth child

During the trial, Pearce twice asked the judge for permission to address the jury but was refused.

He was found guilty and imprisoned for 3 months.

Here is the newspaper report on his trial.

The Sydney Herald

New South Wales, Australia.

Thursday 22 November 1832

MONDAY.—Before the Chief Justice, and the usual Commission.

Villiers Pearce was charged by information with writing and publishing a false, scandalous, malicious, infamous, filthy, and obscene libel, of and concerning Dr. Wardell, Robert Foster, and Sarah Foster, with intent to injure, defame, and vilify, and to bring them into infamy and disgrace, at Sydney, on the 3rd July. There were numerous other counts varying the form of the information.

Dr. Wardell.—I am a Doctor of Civil Law : my father has been dead for some years; I know the hand writing of Villiers Pearce (letter put in;) that is his hand writing; it is directed to my clerk, Mr. Foster; he was my clerk on the 30th July: the passages of the letter apply to him.

[Here the Doctor read various passages, which are totally unfit for publication, and applied various inuendoes to them.]

My father has been dead eleven years ; he lived in Westbourne Place, Sloane Square; I took my degree of Doctor of Laws at Cambridge, upwards of nine years ago.

Cross-examined by Mr. Keith.—Mr. Pearce introduced himself to me some time ago, and said that he had married a person who was related to a person that had married my sister; I had no letter of introduction with Mr. Pearce, but I remember one passage in a letter that I received from England---

" Mr. Priddle desires me to thank you for your kindness to Mr. Pearce." I saw Mr. Pearce write once at Petersham—on a card on my table; I think, " Mr. Villiers Pearce, from England;" and once I believe in my office; there never was the least quarrel between me and Mr. Pearce; the body of the letter, and the postscript, appears to be all one hand writing; I will relate one circumstance, if you wish it; Mr. Foster, who was in the habit of receiving letters from Mr. P., informed me that he was in a deplorable state at Bong Bong; I said he might go to my farm for the sake of his family; he did so, but I was informed that he used towards me language similar to that contained in this letter, and I was obliged to remove him; after he was in Sydney, about a fortnight, he called upon me, and as I wished to have no altercation with him, I desired him to leave the room; I cannot say that I remember Mrs. Pearce; I do not recollect her features; I never verbally or by letter informed Mr P. of what I had heard respecting his conduct towards me; the letter to me was received two days before that of Mr. Foster, and a third one to a person at Petersham, if possible, in a worse

spirit; an enquiry was then made, and I think it was reported he had sailed in the Defiance; the vessel put back, and I think the first I heard of him was an enquiry made by some party who wished to arrest him; I think he was in the Colony at the time these letters were received.

James Raymond, Esq.—I am Post Master of the Colony (a letter put in;) there is a twopenny post; this letter went through the Sydney Post Office; it bears the stamp; the date of the Post Office mark is the 8th August; it is directed to Mr. Foster, clerk to Dr. Wardell, 42, Pitt-street; John McStravack was the postman who delivered letters to that part of the town.

John McStravack.—I am a letter carrier belonging to the Post Office, and was so in August last; I deliver the twopenny letters; Upper Pitt street is in my district; I remember delivering a letter to Mr. Foster, in Pitt street, in August last (letter put in;) I think this is the letter; I understood Mr. Foster to be Dr. Wardell's clerk.

Robert Foster, examined by Dr. Wardell.—I am your clerk, and was so at the time the letter was received; I am married to Sarah Foster, who is mentioned in this information; in August I received this letter, either on the 8th or 9th; I received it from the last witness; I drew his attention to it at the time, because I thought it was a similar letter to that received by you two days before; I opened it in his presence ; it is addressed" Mr. Foster, clerk to Dr. Wardell, 42, Upper Pitt street;" I know the defendant's hand writing ; I have seen him write, and received many letters from him; this letter is in the hand writing of Villiers Pearce.

[Here witness read various ex- tracts, and applied the inuendoes.] The passages throughout the letter where the name of Dr. Wardell occurs, refers to you.

Cross-examined by Mr. Keith.—If I did not know the hand writing of Mr. P., yet from what I heard from other sources, I should still believe him to be the author; Mr. P. called upon me, and I told him before I should speak to him, that he must explain what he had said; he replied, saying how he had been duped by Dr. Wardell; I told him it was false his own letters contradicted the assertion; he then made use of a milder expression than dupe; he never before used any improper language to me respecting Dr. Wardell; he said that what people said he had repeated respecting me was false; I could not say that the superscription of the letter is his hand writing, but my name is at the bottom of the first page, in his hand writing; I received this letter either the 8th or 9th of August, and previous to receiving that, Dr. Wardell received one; I found then that he had sailed in the Defiance; I never quarrelled with Mr. P.

[The letter was here read by the Clerk of the Court.]

Cross-examined by Dr. Wardell.—I never quarrelled with Mr. Pearce, nor I was aware that you were so situated towards him, that you could have quarrelled.

By a Juror.—I think the letters were so timed, that he should escape from the Colony before they were delivered; I think this from their being dated July, and not delivered till 8th August.

By Mr. Keith.—After the Defiance returned, I met with Mr. P. in a public-house; a constable was with me with a warrant; he has been in gaol ever since, I believe, for want of bail; he has a wife and two children, to my knowledge, and I think he said he had some in England.

Dr. Wardell recalled.—My father's name was Robert.

This closed the case on the part of the crown.—

Mr. Pearce wished to address the Jury himself .— His Honor observed, that having Council to examine his witnesses, he could not be allowed to address the Jury himself. If he had examined the witnesses himself, he might have addressed the Jury, and if a point of law had arisen, that might have been argued by Council; the King v. White, the decision of Lord Ellenborough, reported in 3d Campbell 98.

Robert Hayes.—I know defendant ; on the 8th of August he was off Mount Dromedary; I am master of the Defiance; we sailed from the King's Wharf on the 28th July, and returned to Sydney on the 12th August, having been dismasted off Bateman's Bay.

Cross-examined.—Any person having written letters before that, they might have been put in subsequently. We sailed from Watson's Bay on the 3d of August, and had no communication with the shore in the mean time; I reached Botany Bay on the morning of the 4th, where I laid wind bound till the 7th, when I sailed; I had no communication with the shore, except the customs' boat, which came off; I think Mr. Pearce has a brother here he brought Mrs. P. on board; that was on the 28th July.

Dr. Wardell.—I think Mr. Pearce did not bring letters of introduction from my sisters to me; he did not call upon me several times with a mild demeanor, requesting to know why I turned him off the farm at Bathurst; I think he wrote one or two letters to me, which required no answers; Pearce did not in direct terms insinuate any thing to me prejudicial to Mr. or Mrs. Foster.

This closed the defendant's case, when Mr. Pearce again attempted to address the Jury, but was again overruled by the Court.

The Chief Justice put the case to the Jury on the following points :—

first, whether the matter was libellous in its character—that is, whether it was intended to vilify the character of Dr. Wardell, his deceased father, or Mr. and Mrs. Foster;

again, whether there was sufficient proof of the handwriting, and then

whether there was proof of the conveyance of the letter to the Post Office, to be conveyed to the house of Dr. Wardell.

The Jury, without retiring, found a verdict of guilty.

Shortly after his trial, Villiers Pearce wrote to the Sydney Gazette in protest. They declined to print his letter.

The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser

Thursday 22 November 1832

We have received a letter from Mr. Villiers Pearce, on the subject of the information against him for libel, on the prosecution of Dr. Wardell. Mr. Pearce is evidently a gentleman of warm temperament. He is labouring under a sense of real or imagined injury - we do not pretend to say which - and we are of opinion that the best turn we can do him at present, is to withhold the publication of his letter.

The Currency Lad

Sydney, New South Wales

Saturday, 24 November 1832

Mr. Villiers Pearce then appeared on the floor of the Court, to receive its judgment for a false, scandalous, and malicious libel on Dr. Wardell and others, of which ho had been found guilty last Monday. The defendant spoke at some length in mitigation of punishment, alleging various supposed grievances and disappointments by way of extenuation.

In reply to this statement, tho Doctor wished to have read to the Court some letters which he held in his hand, in which tho defendant was said to have expressed different sentiments; the Court, however, declined receiving them, as the observations of the defendant having been merely assertion, no documentary evidence could be requisite or allowable in aggravation.

The Chief Justice then addressed the defendant at some length on the offence of which he had been convicted, and which his Honor said was not merely a vindictive, but a wicked production. The statement he had just made afforded but too plain a proof that he was a man of revengeful passions; and even supposing all he had now advanced to be true, it could afford no palliation for entering the graves of the dead to hold up their memories to obloquy; for attempting to sow discord between the nearest kindred that human nature recognised; or for seeking to destroy the social feeling in relations of business.

It was a remarkable circumstance. His Honor continued, that not one of the alleged grievances this day pleaded appeared on the face of the letter, which consisted only of attacks on the private character of the individual libelled.

It was evident, however, that the defendant laboured under some extraordinary temperament, some mistaken idea, and charitably imputing to such an extent as the Court might some allowance for human frailty, but more particularly taking into: consideration what had appeared in evidence, his very low funds, and tho unhappy inconveniences which his innocent wife and family must suffer as the consequences of his misconduct, they would take the most lenient possible view of his case; and therefore ordered and adjudged that he he further imprisoned in H. M. gaol of Sydney for three calendar months, and at the end thereof to enter into his personal recognisance for his good conduct during the ensuing twelve months, in the sum of £ 100.

The following year Villiers Pearce returned to London with his family.

The Sydney Herald

New South Wales, Australia.

Thursday 18 April 1833

Departures

For London, same day, the ship Edward Lombe, Captain Whiteman Freeman, with 546 bales of wool, 200 tuns of oil, 85 bales of flax, &c.

Passengers, Dr. Watt, R. N., Madame Rens, Madamoiselle Rens, Mrs. Cooper, Mrs. Johnson, Mr. James Simmons, Mrs. Simmons, family, and ser-

vant, Miss Keith, Mr. Wills, Mr. Villiers Pearce, Mrs. Pearce, and 3 children, Mr. James Mapleton, Mr. William Cass Bowles, Mr. Henry Tebbutt, Mr. James Mark Nolah, and Mr. John Rafferty.

Less than two years after returning to London, Villiers Pearce was once again before the magistrate. This time as defendant.

He successfully brought a case against Major-General Ralph Ouseley, accusing him of assault.

The case was widely reported in the London press and The Sydney Herald picked up the story,

The Sydney Herald

New South Wales, Australia.

Monday 23 March 1835

MIDDLESEX ADJOURNED SESSIONS.

Before B. ROTCH, Esq. M. P., and a Bench of Magistrates.

Major-General Ralph Ouseley, of the Portuguese service, was indicted for violently assaulting Mr. Villiers Pearce.

Mr Adolphus conducted the prosecution & Mr. Clarkson defended the Major-General.

The case occupied the attention of the Court seven hours.

Villiers Pearce, examined by Mr. Adolphus.—On the 1st of July the defendant engaged furnished apartments in my sister's house, in York-street; subsequent to which the defendant conducted himself in such a manner as caused my sister to request I would, in the absence of our father, make inquiries at the General's last residence as to his character.

I said so, and such proving highly unsatisfactory, I returned on the evening of the 3rd of July and communicated to my sister the result of my enquiries; the conversation was in their front parlour, and spoken in a moderate tone of voice, during which the General burst open the door, and in the most impetuous manner exclaimed

—"What is all this about?"

I replied—"Do you imagine Sir, by this outrageous conduct, you will intimidate us? We are respectable, and recollect I am the son of as old an officer as yourself."

The defendant then struck me a tremendous blow on the left eye, which closed it, following his hits up about my face and body. From the great advantage of the defendant in strength and stature, I found it difficult to defend myself.

My sisters who were much alarmed and agitated, endeavoured to screen me, and in doing which they were much injured. The General got one of my fingers in his mouth, which he nearly severed.

Cross-examined by Mr. Clarkson—My father is a senior captain in His Majesty's Royal Marine forces. My sisters have a private business in the millinery and dress making.

My father served in most of the action's in the late wars, particularly in the East Indies, under the late Admiral Sir Edward Hughes. He has been repeatedly wounded. My eldest brother is a first lieutenant.

When I was a lad I was a mid-shipman. Subsequently was three years on the plantations at Jamaica and other West India Islands, as overseer and book-keeper. I am a married man and have five children.

I have lately returned from New South Wales with my family, in which colony I held two Government appointments, and was four years absent from England.

I am now a reporter to the newspapers. I will swear that the General attacked me first; I had never seen him before the night in question. No improper epithets were used by myself and sisters respecting the General during our conversation in the parlour.

I will swear that no compromise has been attempted with the General since the affair. I do not reside in my sisters' house.

By the Court—The case was heard at Marylebone Police-office, and Mr Rawlinson advised me to indict the General.

Misses Eliza and Henrietta Pearce were examined, and corroborated the testimony of the prosecutor as to the assault, and in answer to some of the questions put by the Court said, that had the General conducted himself properly in the house, they would have been glad to keep him as a lodger.

Louisa Benson, a servant, swore that the same day the General came to Miss Pearce's he made improper overtures to her, which she communicated to the Misses Pearces.

It appeared that the General had attempted to vilify the character of the Misses Pearce and defame their house, after he committed the assault.

Mr Clarkson, for the defence, called four labouring men, whose testimonies were very contradictory.

Elizabeth Laxton, the General's principal witness, gave evidence which fully bore out that given by the prosecutor and the Misses Pearce.

The Chairman summed up at considerable length, commenting upon the nature of the defence which had been set up, and which had injured the defendant's case. He drew the attention of the jury to the respectability of the witnesses for the prosecution, and how natural it was, after what they had heard of the General, that the conversation in the parlour should take place.

Mr. Clarkson observed that he could not assert anything prejudicial of Mr. Pearce and his family.

Mr. Adolphus, in a long address to the jury, remarked whether it was probable that the children of a veteran should be brought up to such vile habits as to perjure themselves for the purpose of punishing the defendant.

The jury retired for three quarters of an hour, and on their return into Court delivered a verdict of Guilty.

The Chairman addressed the defendant and said that his conduct had been so disgraceful that himself and brother magistrates considered that it was incumbent on them, for the public peace, that he should be severely punished.

The Sentence of the Court was to pay £100 to the King, to find sureties himself in £500 and, two in £100 each, and to be imprisoned till the said fine was paid and sureties entered into.

— Times.

The Tasmanian (Hobart Town)

Friday 29 June 1838

DIED —On the 24th Jan.. of consumption (brought on by privations and sufferings during a voyage round the world, and travels in the interior of " New South Wales"), Emma Louisa, aged 34, the beloved wife of Mr. Villiers Pearce, formerly of the Post-office department in the above Colony, leaving a disconsolate husband and six young children to mourn their irreparable loss.

Here’s the transcript of his Old Bailey trial for forgery. I’ve reproduced it here in full.

Proceedings of the Central Criminal Court.

26th October 1846.

BRIDGET SULLIVAN. VILLIERS PEARCE. Deception; forgery, Deception; forgery.

2043. BRIDGET SULLIVAN was indicted for feloniously and knowingly uttering a forged order for payment of 15l., with intent to defraud Edward Majoribanks and others; and VILLIERS PEARCE as an accessary before the fact.

MESSRS. DOANE and ROBINSON conducted the Prosecution.

JOHN BLENKINSOP . I am cashier at Coutts and Co.'s bank—Mr. Edward Majoribanks is a partner in the house—there are other partners—on the 27th of Aug., about four o'clock in the afternoon, the prisoner Sullivan came to the banking-house, and presented this check for 15l. for payment—(read—dated 25th Aug. payable to Mrs. Wallis or bearer, 15l.; signed Caroline Queens-berry, and endorsed C. Wallis)—the Marchioness of Queensberry has an account at our house—I asked Sullivan what she would have for it—she replied very quickly, "Gold"—I then walked round the counter, and desired her to step into the back-room—she did so—on the way I asked her if she re-ceived it for herself—she said, "No"—I asked for who she received it—she

said, "For a man"—I asked if she knew the man—she said, "No"—I think I asked her if she knew where the man was—she said, "outside"—I then called a messenger and desired him to fetch a policeman—lam well acquainted with the Marchioness's writing, and declare this not to be her writing—I produce eight checks which have been paid previously.

JAMES GOODWIN . I am porter at Coutts' bank. On the 27th of Aug. I saw the prisoner Sullivan at the counter—in consequence of instructions, I accompanied her to Charing-cross—I walked a little way before her, but near her—Sinnott, the policeman, was also in attendance—as we went along she gave me a description—she said it was a tall man with a black frock coat on, with sandy hair and whiskers, and hair on the upper lip—she did not say what she was to meet him for—we went to Charing Cross, and then to the fountains in Trafalgar-square—she said that was where she was to find him if she did not meet him on the road—we went to the fountains—there was no man there answering that description—I waited a minute or two—she did not tell me who she was—I did not hear her say what her name was, or where she came from.

WILLIAM SINNOTT (police-constable F 91.) In consequence of directions from Goodwin I watched Sullivan—I heard her describe the person she was to meet—I saw no one answering that description—she was afterwards given into my custody—I produce a letter which I received from the female searcher at the police-station—I had heard nothing said about that letter before—I heard her say her name was Bridget Sullivan, that she came from Skevenden, in the West of Ireland, on the Tuesday previous, by a steamer, to somewhere about London-bridge, that she had a husband somewhere about Chelsea, as she heard, and she had come in search of him, she could not succeed in finding him there, walked back again in the evening, and walked about all night to look for him, she was then going down to Whitechapel to see if she could find him, and was on her road there—as she came past the bank she said she had no relations or acquaintances in London except her husband, that she was never in London before in her life.

Cross-examined by Ms. BALLANTINE. Q. When were you called to go with her? A. About four o'clock in the afternoon—I was fifteen or twenty yards behind Goodwin—I kept them in sight—I was at the bank before I went out—I was up with them when she told me all this—she said it in the square when I came up with them, not in the presence of Goodwin—I overtook them in the square—the conversation I had with her was at the banking-house on the day she was given in charge—Mr. Bush was present—Goodwin was not; nobody bat Mr. Bush, who asked her a few questions—he did not regularly cross-examine her.

Cross-examined by MR. DOANE. Q. Did Mr. Bush warn her as to the answer she gave when he questioned her? A. I cannot recollect.

JOHN BLENKINSOP re-examined. Mr. Bush had come into the bank accidentally on business at the time.

MARGARET PYKE . I am searcher at Bow-street police-station. I was directed to search Sullivan—she wanted to go to the water-closet—I searched her, and found this letter (marked A) in some part of her gown-sleeve—I shook the gown-sleeve, and it fell from it—when I found it, she said they had got the other paper, and that was of no use—she did not propose that I should do anything with it.

JOSEPH THOMPSON (police-constable.) On the 20th of Oct, I apprehended the prisoner Pearce at No. 1, Millman-place, Millman-street—I told him I apprehended him for being confederate with Bridget Sullivan, his wife, for uttering a forged check on Coutts' for 15l.—he said it must be a mistake,

he had no wife, she had been dead six years—I told him he was Villiers Pearce, the man I wanted, and he must go with me—I took him to the station—he gave his address No. 58, Eagle-street, Red Lion-square—I went there, and found a good many papers, and this among the rest—(produced)—I found these letters on him—he wanted to give them to his sister.

CAROLINE, MARCHIONESS OF QUEENSBERRY . I principally reside at Coton-house, near Rugby—I have had correspondence with Pearce and other members of his family, and have occasionally written letters to him inclosing remittances—I have inclosed checks to him—one of the letters found at his house is one of many letters I sent him—it contained a check—no part of the check produced is in my handwriting—I never authorised him to write that or any check—it is not a very good imitation—I did not write any part of this letter—(looking at one marked A)—I have received many letters from Pearce, and written answers to them, and, to the best of my belief, this check ii written by him.

Cross-examined. Q. I believe your ladyship never saw the person who signed himself Pearce? A. Not to my knowledge—I have had no personal communication with him on the subject of the letters—if those letters did come from him, I think I can swear the check is his handwriting—there is an imitation of my handwriting in the signature only.

MR. DOANE. Q. Did you receive these letters in the name of Pearce? A. Yes, and wrote answers to the addresses named in them.

MR. BALLANTINE. Q. Did you write the answers yourself? A. Always, and gave them to my servant to put in the post.

WILLIAM DYATT BURNABY . I am chief clerk at Bow-street police-court.

Sullivan was brought there on the 28th of Aug.—she made this statement, which I took down in writing—(reads)—the prisoner says,

"As I was passing along the street I went up to the gentleman and asked the way to Whitehall; he said, 'What do you want to go there for, my good woman?' I said I wanted to go there to see my husband; he walked down and said, 'I'll show you,'—when we got by the rails be took those papers out of his pocket and said, 'if you will go in there' (pointing over the way,) 'and bring me what you get for this;' he asked me whether I could read or write, I told him I could not; he then gave me the two papers, and said, 'You need not show the big paper;' he folded the little paper, and told me to take it to the gentleman at the counter, and that I need not show the other paper unless I was asked for it; and if the gentleman asked me what I would take I was to say, 'Gold;' when he gave me the papers I said, 'lama stranger here, and don't like to go in;' he said, 'Oh, you foolish woman, I am known in that banking-house, and the gentleman thinks I am out of town, and I don't like to go in; when 1 went in 1 put the paper on the counter, and the gentleman asked me what I would have; I said, 'Gold;' he then took me into a parlour and asked me whether it was for myself; I said no, a gentleman had given it to me; the gentleman who gave it me said he would wait up and down till 1 came out, or he would be at the waterfalls if he was not there."

—On the 21st of Oct, the prisoner Pearce was brought in, and made this statement—(reads)—

"The notes I received from Lady Queensberry were not always signed by her ladyship, but some of them commenced, of Lady Queensberry;' her ladyship bs"? been in the habit of sending me letters, and occasionally checks, for the last fiw years; this woman came to me five or six years ago, upon the death of my wife; she came as my housekeeper, and to attend on the children, not being able to do without such a person, being about from morning till night, in my occupation I as a reporter—her conduct became exceedingly discreet, steady, and respectable; and notwithstanding my great poverty, I still kept her in my service, as I was enabled to keep my home with her assistance in comfort; I left her to go to the West Indies, and on my return her conduct being so good I married her on the 17th of last June, she having previously given birth to two children; on the morning of the 27th Aug. last she left my home, and I heard no more of her till I heard she was in custody—I solemnly swear I never forged a check on the Marchioness of Queensberry, or sent my wife with one; she hat made herself appear a perfect stranger to me, on purpose to save my character; and being neither able to read or write, she could not know the nature of the document; I have held responsible situations under Government abroad; my wife made this story on purpose to save my name being brought forward on the charges."

Cross-examined. Q. I believe certain letters were produced and alluded to in the evidence? A. Yes—they were not read in the prisoner's presence—they were handed to his attorney to read if he chose—I heard it stated that a copy would be forwarded to the prisoner.

JOHN WINTER . I am a builder, and live in Tash brook-street, Pimlico. In July last both prisoners came to me about taking a house—Pearee spoke—I do not know that I heard Sullivan say who he was—he was not introduced to me by her—they became my tenants about the 13th or 14th of Aug., and lived with me some time—I had seen Pearce between July and Aug.—they both went by the name of Pearce—I missed Sullivan from the house after that—I cannot say when it was, but I noticed repeated knocks at the door—I met Pearce, and told him I wanted to come in to look at the ceilings—he said Mrs. Pearce had been out, and would be home in a day or two—I think that was in Sept.—I did not see her again.

JOHN YOUNG . I am a solicitor, and live in Bloomsbury-square. I have known Pearce about eighteen years—I have corresponded with him, and received letters from him, and have conferred with him on the subject of those letters—I have seen him sign his name—I believe the body of this check to be his writing—(looks at it)—I cannot speak with certainty as to the letter (A.)

Cross-examined. Q. Is there anything remarkable about the character of his writing? A. Yes—I consider there is no disguise about it at all—he is a relative of mine—I corresponded with him about a year ago, and have done so five or six years—it is only till very lately that I have had correspondence with him—it ii two or three years ago, I cannot distinctly recollect how long, hot not within a year I have seen him write—I have a memorandum here, signed by him on the 7th, 17th, and 25th of Aug., 1843—I saw him write on all those days—these are the documents he wrote be name to—I do not recollect seeing him write anything but his name.

----BELL. I am a reporter, and live in Southwark Bridge-road. I am acquainted with Pearce and his writing, and believe this check to be his writing—three years ago he was an occasional contributor to various newspapers—I had attended public inquiries for five or seven years previously, and have had occasion to see him write 150 times—the last time was about four years ago—previous to that I was in the habit of seeing him write pretty constantly—to the best of my belief this letter (marked A.) is his writing—I believe these also to be his writing—(looking at some others.)

Cross-examined. Q. Had you and the prisoner any difference at any time? A. Never—it is four or five years since I saw him write or act as a reporter—I believe he has not been reporting since that—we were occasionally in the habit of reading each others reports.

THOMAS JOHN GREEN . I am a newspaper reporter, and have known Pearce several years as a reporter. I know his handwriting, and believe this

check and this letter (marked A.) to be his also—I also believe these other letters to be his.

Cross-examined. Q. How long is it since you have seen him write? A. I think about three years—I was not very intimate with him, but frequently saw him write, and his copy frequently passed through my hands.

THOMAS WATSON . I am a manifold paper-maker. I have known the prisoner seventeen or eighteen years—I have frequently seen him write—I believe this check to be his writing—this letter (A.) is his style of writing—I believe it to be his, and these other letters as well.

Cross-examined. Q. You seem to express a doubt about the letter? A. I discover a difference in it, which creates a doubt—it is a broader writing—he did not generally write so broad a hand—I recollect his writing perfectly well—the check is in his ordinary writing, but the letter is broader—the letters are wider altogether—his handwriting is generally close—the words are stretched out—they are larger than his general writing—(letter A. read—"Coton-house, 25th of Aug., 1846: Mrs. Wallace, I received your letter, and now send you a check on Messrs. Coutts' and Co. for 152.; you will let me know by letter the receipt of the same.—Caroline Queensberry.")

SULLIVAN— GUILTY . Aged 35.— Confined Six Months.

PEARCE— GUILTY . Aged 44.— Transported for Ten Years.

Before Mr. Justice Erle.

Old Bailey Proceedings Online. October 1846. Trial of BRIDGET SULLIVAN , VILLIERS PEARCE (t18461026-2043).

Villiers Pearce was one of 307 convicts transported to Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania) on the Blenheim. The ship left England on 23rd March 1850 and arrived in Hobart Town on 24th July 1850. You can see the convict register for the voyage here. Here is the entry for Villers Pearce.

The convicts aboard the Blenheim were transported for a range of petty crimes, those recorded include sheep-stealing, housebreaking, burglary, forgery, desertion from the army, theft and pocket-picking.

They were at sea for 123 days. Charles Henry Fuller was the ship’s surgeon and his medical journal survives.

On arrival in Van Diemen’s Land, each prisoner was recorded in the register of convicts.

Here is the entry for Villiers Pearce:

Name: Pearce, Villiers

Where tried: Central Criminal Court

When tried: 26 October 1846

Sentence: 10 years

Age: 48

Height: 5’ 7”

Religion: Church of England

Read or Write: B (both)

Married of Single: Married

Children: 9

Statement of Offence: forging a cheque for £15 Marchioness of Queensbury -

Trade: reporter

Native Place: Brompton

Comptroller-General of Convicts: Indent of convicts arriving in Van Diemen’d Land on 15 October 1845 per Stratheden; and on 25 August 1846 per Lord Auckland and on 24 July 1850 per Blenheim.

You can see the original convict register entry here.

Here’s the transcript of his Old Bailey trial for returning to England before the 10-year term of his transportation had expired.

It includes Pearce’s full statement, which was so remarkable that it appeared in newspapers across Britain and the colonies.

Proceedings of the Central Criminal Court.

27th February 1854

365. VILLIERS PEARCE , feloniously being at large before the expiration of the period for which he had been ordered to be transported.

MR. RYLAND conducted the Prosecution.

JOHN GUNN (police-sergeant, G 8). In consequence of information I received on Sunday, 12th Feb. I went to No. 27, Garnault-place, Clerkenwell, which is the house of the prisoner's sister—I found the prisoner there, in the kitchen—I said to him,

"You must come along with me, Mr. Pearce"

—he said, "What charge have you got against me?"

—I said, "The charge against you will be, returning to this country before the expiration of the term of your transportation"

—he at first said, "I have never been out of England;" but on the way to the station, he said he thought he had done enough, and undergone hardships enough, in Van Diemen's Land and other places, during his period of transportation—he was a good deal in liquor—I have here a copy of the paper, which we received from Hobart Town, containing his description.

WILLIAM SINNOCK (policeman, F 91). I produce a certificate

—(this being read, certified the conviction of Villiers Pearce at this Court, for felony, in Oct., 1846, and then proceeded to state that the said WILLIAM Pearce was ordered to be transported for ten years)

—I was present at the trial—the prisoner is the person who was so tried—he was convicted in my hearing—I heard the sentence passed upon him—it was ten years' transportation—he is the man.

(The prisoner's statement before the Magistrate was read as follows:

"At the period of the offence for which I was convicted I was suffering from the most acute pecuniary distress, with a wife and large family of children, a series of misfortunes; the most heavy was the death of my second wife, by which I lost an annuity of 150l., with a great falling off, notwithstanding all my exertions in my occupation as reporter to the public press, brought about mainly the distress in question; previous to the commission of the offence.

I had through life borne an irreproachable character; in early life, from 1818 to 1822, I held some most responsible appointments in Jamaica and other West India Islands; from 1829 to 1834 I held the appointment of Magistrate's clerk and postmaster at Bong Bong in New South Wales; afterwards was superintendent of large farms at Bathurst, over the Blue Mountains, in the same colony; at the latter period I had a wife, and family of young children; the former, a most amiable partner, I had the misfortune to lose in 1838, leaving me with seven young children; my connections are most respectable; my late father was an officer of rank, and of very meritorious services; my eldest brother is at present a major in the Royal Marine corps.

I was convicted in October, 1846; was three months in Millbank Penitentiary, at which period fears were entertained that my intellects would become impaired in solitary confinement; subsequently I was three years and two months in the Warrior convict ship at Woolwich, during which period I was employed on the Government works in the dockyard.

I was sent abroad in March, 1850; at Millbank and the Hulks I had the best possible character, as also on my arrival at Hobart Town, Van Diemen's Land, after a passage of four months—on my arrival I received a ticket of leave, which I retained until I left the colony, never having forfeited the game for a day by any kind of insubordinate conduct; my motive in leaving Van Diemen's Land was to proceed to the gold-diggings, in the hope I might be successful, and better the condition of my family at home, who are in very impoverished circumstances, but, although my exertions were very great in California, Victoria, and New South Wales, I was unsuccessful; it is true I made occasionally some money, but I was robbed of it on the road by armed bush-rangers, and frequently ill-used and robbed at Melbourne and Geelong by the worst of characters.

I was shipwrecked twice, and once burnt out at sea, the first time in Torres Straits, between New, Holland and New Guinea, on a reef of coral rocks; upon this occasion I lost between 70l. and 80l. in cash, and all my luggage; eleven of us only got ashore, out of a ship's company of twenty-seven, chiefly Lascars, Malays, and Chinamen; after thirty days great suffering and privation, we were picked up by an American whaler, and ultimately reached Sydney, New South Wales.

I was subsequently wrecked in a brigantine, called the Triton, going from Melbourne to Adelaide, and lost all I possessed in the world, having another very narrow escape of my life; in returning from San Francisco to Melbourne in a vessel called the White Squall, she caught fire about 350 miles from Tahiti (formerly called Otaheite), we were obliged to abandon her, and took to the boats, but a great number of the crew and passengers perished by fire and water, the survivors in the boats reaching Tahiti in about eight days, in a state of great exhaustion, many of whom died from the effects of the same; I had the misfortune to lose nearly all I possessed upon this occasion; on reaching Melbourne I was very ill, and went into the hospital; I left in about five weeks, intending to go again to Mount Alexander diggings, but owing to ill health, bad state of the roads from the floods, and limited means, I abandoned such.

I had a twelvemonth before been to Ballarat, Mount Alexander, Forest Creek, Bendigo, and many other diggings, but at this time no police was organized, or gold escort troopers, consequently nearly all the unfortunate diggers were robbed of what they got, by hordes of bushrangers, well mounted, and armed with revolvers and other weapons to the teeth; in returning to Melbourne from Forest Creek the last time, I was beat, stripped, and robbed of all I had, in the Black Forest, about half way between Melbourne and Mount Alexander.

I left Melbourne in the brig, Kestril, for Sydney, New South Wales, at which place I was acquainted with many respectable parties, some of whom I had known as far back as 1829, when I first went to Sydney with my wife and children; the Kestril put in at some of the settlements of New Zealand, at one of which (Auckland), was laying a barque, bound for England, in want of hands; the temptation was great to reach my dear family, for which I had mourned ever since I met with my misfortune; I shipped myself as ordinary seaman and assistant steward; we left the settlement in July, with a miserable crippled ship's company, and made a very severe passage round Cape Horn in the winter season, we carried away masts, sails, rigging, boats, bulwarks, stauncheons, &c., &c., some of the crew were lost front the yards, and most of us were frost bitten; we put into Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, South America, to refit and provision; we proceeded on our passage, crossed the Equator, touched at Terceira, one of the Azores, for two days, and reached England in Sept., after a severe passage of four months and twenty-six days from New Zealand.

Under all the circumstances of my present unhappy condition, I humbly hope the legislature will humanely consider the long, severe, and various description of punishments I have undergone since my conviction; I would also most respectfully call the attention of the authorities to the fact, that the offence for which I have so severely suffered, was the fist deviation from strict rectitude during my life, and that I have never since, upon any occasion whatever, received a second sentence, even of the most minor description; it was only required of me, by the then regulations of the service, that I should serve five years upon the public works at Woolwich; on my embarkation for Van Diemen's Land, I had done three years and four months; if I had completed the remainder twenty months I should have been discharged from the dockyard a free man.

I also humbly beg to state, at the time I left Van Diemen's Land, six years after my conviction, I was entitled, by the regulations of the service, to a conditional pardon, which would have left me at liberty to leave the colony without further restraint.

I beg to state, that during the period of three years and four months I was at the hulks I worked in all the gangs in the dockyard; upon several occasions I received severe injuries, some of which requiring me to be sent to the hospital ship; I was ruptured by carrying heavy weights, the effects of which I have frequently felt since, and do to the present day; during the two periods when the cholera raged at the hulks, I attended upon the sick at the hospital ships.

I humbly implore the Government will have compassion upon me, for the sake of my numerous and respectable family, for my great mental and bodily sufferings since my conviction, and for my present weakly, worn out, debilitated state of health, and award me a mild sentence.

During my captivity and absence, my unfortunate wife has suffered from great destitution, and buried two of her children; she is again bereaved of me in a distressed condition, with her only surviving child, a little girl of ten years of age."

JOHN GUNN re-examined. I have heard that statement of the prisoner read; I heard it before the Magistrate—I have not made any inquiries about it; no doubt it is true, but it all happened abroad—I knew him before he was transported; he was then a reporter—I knew him then to be a respectable man—I knew him some years before his conviction—he used to report for the public press, at the different police courts—we received a large placard from Hobart Town, which was posted up in the charge room, so that all the officers could see it—it was not in consequence of information from any of the police that I went to take him—I cannot say from whom I received it; but an anonymous letter was sent, we never

knew by whom, stating he was at large; it was from somebody that knew him, no doubt.

William Anderton, a fur skin dresser, of 4, Red Lion-street, Clerkenwell, and Catharine Anderton, his wife, deposed to the prisoner's good character prior to his conviction in 1846, and expressed their belief of the truth of the statement read.

MR. METCALFE submitted that from the defective form of the certificate, there was no legal proof that Villiers Pearce was the party sentenced, and that the prisoner was entitled to an acquittal.

The RECORDER considered the objection to be well founded, and the Jury found the prisoner.

NOT GUILTY .

Old Bailey Proceedings Online. February 1854.

Trial of VILLIERS PEARCE (t18540227-365).

In 1856, he published his story in a 16-page pamphlet titled, The Trials and Vicissitudes in the Life of Villiers Pearce. Printed and published by H. Elliot (1856).

Death indexes record the death of Villiers Charles Pearce on 25 April 1862. He is buried in the Brompton Cemetery in west London.

The death was registered at St George Hanover Square, London, United Kingdom.

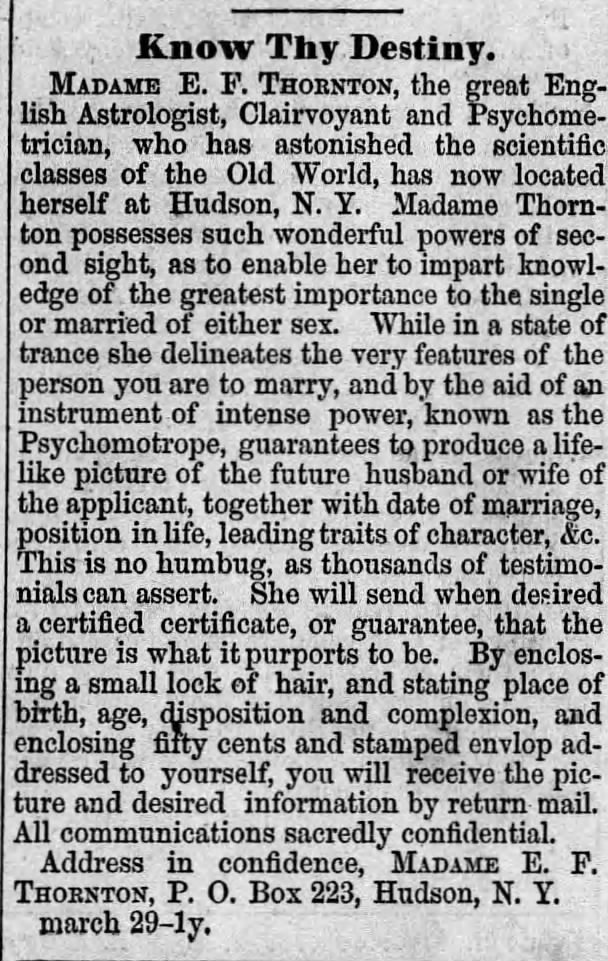

Victorian spam

I randomly came across this little advert in the archives of The Record, the local newspaper of South Melbourne in Australia.

It was so odd and reminiscent of today’s Viagra spam emails that I thought I’d share it.

The Record

South Melbourne, Australia

Friday, 12 September 1884

To all who are suffering from the errors and indiscretion of youth, nervous weakness, early decay, loss of manhood etc I will send a recipe that will cure you, FREE OF CHARGE.

This great remedy was discovered by a missionary in South America.

Send a self addressed envelope and six pence to prepay postage to the Rev. Joesph T Inman, Station D, New York City. USA.

I guess this is the Victorian ancestor of all those scam emails we get today.

Someone, somewhere must’ve fallen for it.

Turns out the ‘Rev Joseph T Inman’ was a legendary 19th-century fraudster. It seems he was involved in occult fraud and operated under a series of weird and wonderful aliases.

One of his stranger aliases was ‘Madame E. F. Thornton, the great English Astrologist, Clairvoyant and Psychometrician’, who advertised a fantastically named fictional contraption called a Psychomotrope.

Raymond, Mississippi. Friday, 19 April 1867.

The US Postal Service eventually opened an investigation into him and uncovered a network of fake newspaper ads designed to defraud the gullible.

It seems Inman picked up the cash mailed in by the unsuspecting and, as one theory goes, his real business was the re-sale of respondents’ names, addresses and personal information, presumably to other fraudsters.

Sound familiar ?

Triumph of the Will. 1935

Channel hopping last night I stumbled across Leni Riefenstahl’s 1935 film, ‘Triumph of the Will‘ on BBC4.

It’s Nazi propaganda at its most mesmerising. A masterpiece of imagery.

Riefenstahl produced and directed the film about the 1934 Nazi Party Congress at Nuremberg.

Hitler is the star and the film consciously builds him up as god-like Fuhrer.

Technically it’s brilliant for its time. Her hypnotic shots of marching troops are truly compelling. The crowds seem wild with admiration as they salute Hitler and the Third Reich.

The film ends with Hitler’s speech to the troops at Nuremberg. I must say his speech, captioned in English, didn’t make much sense and seemed more random sentences than a coherent call to arms.

The overwhelming message of the film is that Hitler and the Nazi movement are the living symbol of the reborn German nation.

It’s un-equalled cinematic propaganda and now very chilling to watch. We know what is going to happen and it’s disturbing to see so many people swept up in the euphoria. Their blind compliance and worship of Hitler is genuinely frightening to witness.

Even today, 70 years on, Riefenstahl’s skilful deployment of cinematic tricks and epic scenery portrays the terrible magnetism of Hitler and the Nazi party.

His persona and the martial power of the Third Reich seem strangely captivating. Like an irresistible drug, the viewer is compelled to believe the propagandist’s illusion.

Surely, no one watching this film in 1930s Europe could conclude Hitler might be appeased. The film shows the Fuhrer presiding over a fanatic war machine. Negotiation and agreement with Hitler must have seemed futile.

Homo floresiensis

Scientists have discovered a new species of human. Long extinct, the 3-foot people lived on a tiny island in Indonesia until at least 12,000 years ago. They evolved in isolation and developed long arms, probably for climbing trees.

The new species has been named “Homo floresiensis” or “the Hobbit”. Archaeologists have uncovered an 18,000-year-old specimen along with six other individuals.

The amazing thing is the legends of the local people describe ‘Ebu Gogo‘, or little people about one metre tall, hairy and prone to “murmuring” in a strange language.

The most recent ‘Ebu Gogo‘ story is about 100 years old…

What an intriguing find. Could there even be any left alive…

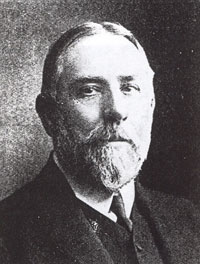

Great-uncle Ant

Amazing discovery today – I got hold of a photo of ‘great-uncle Ant’ !

I remember my grandfather talking about a character who he affectionately referred to as ‘great-uncle Ant’. I had no idea who he was but knew that he was the brother of my grandfather’s grandfather.

I have been researching my family on and off for the last 10 years and have uncovered a fascinating story.

The family emigrated from Dublin to Melbourne, Australia in 1853, probably in search of gold. They ran a pub, worked in construction and generally prospered.

My great-great grandfather went into shipping and became the P&O shipping agent in Melbourne, then Sydney. My great-grandfather was born in Melbourne and trained as a doctor. He studied in London before moving out to Cairo to set up the Egyptian Medical School.

Anyway, I knew that my great-great grandfather’s younger brother, Charles Anthony Madden, moved from Melbourne to Western Australia in the 1880s and didn’t know much more about him.

I was hunting around online to see if I could get any leads on him or his descendants and came across the State Library of Western Australia and did a quick catalogue search.

To my utter amazement, a reference came back for a biography and portrait *gasp* of Mr Anthony Madden of Arthur River. After a swift email inquiry, a very, very nice librarian actually posted me a photocopy of the relevant page with the picture.

It was ‘great-uncle Ant’. My God, he even looks a bit like his elder brother.

One of my winter projects is to write up the whole story and publish it online.

If I get snowed in for a month I might actually get around to it…;o)

ooops…!

A copy of this picture hangs in a little deli I sometimes visit for lunch.

It was taken at Montparnasse Station on 22 October 1895…

I wonder what happened ?!

grandparents…

I have been looking through a box of old family papers and photographs today.

It is poignant to read my grandparents’ letters and see their old photographs. Some of the pictures are over 100 years old !

One of the most striking things is that photos from my grandparents’ childhoods (1900-1920ish) are so similar to those of their children and indeed my own childhood.

Give or take the style of clothing and colour photography, as children we did the same sort of things – play on the beach, pose for pictures with proud parents, play in the garden etc etc……

It’s odd to be able to see photographs of 4 children, knowing that each is one of my grandparents…..without them, I would not be. They were me 100 years ago !

It reinforces my belief in the cycle of life…we are born, develop, pair off, breed, raise young, wither and die.

I can see my grandparents as children knowing how their lives would develop. Knowing who the little girl or boy would marry, how many children they would have, and where they would live and work.

Also when and how they would die. The only difference between them and me is time…..

Their cycle has been completed, mine is still current. They are now the past, I am still the present.

In 100 years someone may be looking at photos of me wondering who was that person, what was his story…. it’s up to me to make it an interesting read !!!